Although ubiquitous computing hardware and software technology is largely available today, we believe one key factor in making ubiquitous computing useful is a framework for exploiting multiple heterogeneous displays, whether fixed or on mobile computing devices, to view and browse information. To address this issue, we propose multibrowsing. Multibrowsing is a framework that extends the information browsing metaphor of the Web across multiple displays. It does so by providing the machinery for coordinating control among a collection of Web browsers running on separate displays in a ubiquitous computing environment. The displays may be "public" (e.g. wall-sized fixed screens) or "private" (e.g. the screens of individuals' laptops or handhelds). The resulting system extends browser functionality for existing content by allowing user to move pages or linked information among multiple displays, and also enables the creation of new content targeted specifically for multi-display environments. Since it uses Web standards, it accommodates any device or platform already supported by the Web and leverages the vast existing body of Web content and services already available. We describe the design and implementation of multibrowsing and a variety of diverse scenarios in which we have found it useful in our test bed ubiquitous computing environment.

Although the Internet has been functional for over 30 years, it was the Web, with its open protocols and end-to-end architecture, that raised the usefulness of Internet-connected computers to a new level and led to the wide and rapid adoption and development of the Internet. In the last few years, we have seen the beginnings of a similar trend: fundamental technologies to enable portable and environmental computing (together often referred to as ubiquitous computing) have become increasingly affordable and mainstream, but are still awaiting a catalyst that will help ubiquitous computing "take off", just as the Web did for Internet-based computing.

An important common feature of ubiquitous computing environments is the presence of multiple display surfaces. For example, consider the iRoom, an experimental conference/workroom we have built as part of the Stanford Interactive Workspaces project to investigate how people interact in ubiquitous computing environments. Largely as envisioned by Weiser [WEI], the iRoom includes three large (whiteboard-sized) touch sensitive screens, a bottom projected table top display, and multiple laptop, handheld and Palm sized PCs, some with wireless connections. The prevalence of multiple display surfaces in such computing environments suggests that a framework that extends the information browsing metaphor to multiple displays may be an important enabler for ubiquitous computing. Such a framework would also have to enable collaboration by allowing multiple users to coordinate browsing across wall-size displays, and by allowing the easy movement of information between users' "private" (laptop or handheld) displays and large-size "public" (e.g. whiteboard-sized) displays.

Web technologies were originally developed for the "one person, one screen" scenario, and during our initial use of the iRoom we found it very awkward to manipulate a number of individual Web browsers in order to bring up a coordinated collection of information across the iRoom's displays. We designed multibrowsing as a general set of mechanisms to view, move and interact with information among the multiple displays. We wanted to emulate the properties that made the Web so successful, and in fact we were able to use Web technologies as a starting point to develop multibrowsing: Specifically:

While we initially designed the system for the iRoom, it has proved flexible enough to use in offices with multiple desktop PCs, and to prototype content for iRoom viewing across collections of laptop computers. We envision the system as being useful in most ubiquitous computing environments.

This paper presents the multibrowsing system and its goals, and gives some examples of how we have found it useful in the iRoom, where it has been in day-to-day use for more than a year now. Next, we present the details of our implementation. We follow with some of the ways we hope to expand the system in the future to make it even more general, and conclude with some discussion of the different use metaphors we have seen and the system's strengths and weaknesses.

The goals of the multibrowse system include the following:

In this section we present a simplified conceptual description of how multibrowsing works; we provide more details and implementation specifics in section 4. In the following discussion, a display is an area for displaying pixels, and the display is usually bound to a specific device, which may be a handheld PC, laptop, or (as in the case of our touch sensitive SmartBoard screens) a PC integrated with the display. All of our devices are assumed to be connected to a network, hence they can communicate with each other and with other entities on the network. We designed multibrowsing with a geographically localized environment in mind (and therefore a local-area network), but since all communication among multibrowsing entities use existing TCP/IP-based protocols (as we explain in section 4), the following architectural description can also be applied to a wide-area network without loss of functionality.

Each network-connected device that wants to participate in multibrowsing runs a standard Web browser on its associated display. Essentially, multibrowsing works by having each such device participate in a publish/subscribe communication system implemented on top of the network. The devices exchange multibrowse events that direct the individual browsers on each display to perform actions such as displaying a particular remote URL, opening a new window on that display, and so forth. The event system we use is not Web-specific-- it is also used for other, non-multibrowsing applications in the iRoom-- therefore, the multibrowsing system also includes two pieces of middleware to connect the event system to Web browsers. The first of these is a server-side executable that allows events to be posted using standard Web mechanisms such as "fat URL's" and form submission. These fat URLs can also be constructed on-the-fly from ordinary URLs using our custom browser plug-in (henceforth referred to as multibrowse plug-in). The second is a daemon process that must be run on each device that is to be "remote controllable"; this daemon subscribes to events in our event system and uses existing support for local control of a running browser to effect the desired browser action, such as visiting a particular URL. The resulting system has the following properties:

These properties facilitate many interesting usage scenarios, some of which we have used in the iRoom. We describe some of these in the following section to motivate the implementation details which we then discuss in section 4.

Although the multibrowsing system is flexible enough to be used in many environments, it has currently been used in two main locations:

Next, we present several examples of how we have used the multibrowsing system. Each example is designed to highlight a certain style of information interaction, moving, or viewing that is enabled by the multibrowsing system. The examples are collaborative research, meetings, presentations, and data interaction. They are presented in order from things that require the least amount of effort beyond deploying the basic multibrowse system to those that would require a significant amount of design and development work by the users of the multibrowse system.

The first example is collaborative research using the web. It demonstrates the usefulness of being able to freely pull up information and move it to different displays, functionality that is achieved by just installing the multibrowse system in an environment.

One of the goals of the creation of the iRoom was to design an environment suitable for ad hoc meetings where researchers discuss ideas, share information, and brainstorm. Over the past year, we have observed that multibrowsing has become an integral part of such meetings. To illustrate this, we will step through the sequence of interactions between members of the of the Interactive Workspaces group in one such meeting. One of the members of the group mentioned that he had heard of a new wireless modem manufactured by a certain company that could be useful for the handheld devices in the iRoom. The other members of the group wished to know more about the new modem. Using the multibrowse plug-in from a browser on his laptop, the original member opened the Web page of the company on SmartBoard1. Meanwhile, another member used a search engine on another touch screen and located a site that summarized the features of various commercially available wireless modems. Information from the various companies was then multibrowsed to the other two SmartBoards so that the group could compare the features of the modems.

All the pages that were multibrowsed in the above example were standard web pages that were redirected using the multibrowse plug-in. Figures 1 and 2 show how the right-click context menu has been extended to allow multibrowsing of links and pages. Figure 3 shows the dialog that allows users to select to which remote display they want to multibrowse the content.

A similar scenario can also be engineered using Web pages created with multibrowsable links. In such a case, one or more members of the group create a corpus of Web pages with multibrowse links that the entire group can jointly multibrowse in order to visualize and understand the material better.

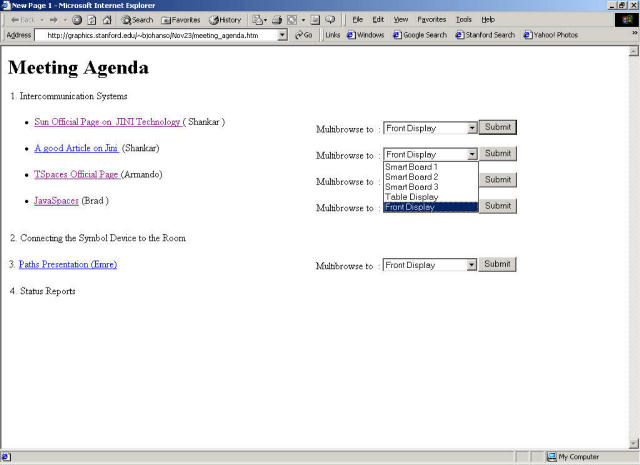

With somewhat greater effort, it is possible to organize meeting materials to take advantage of a multi-display space enabled with the multibrowsing system. Specifically, a customized meeting agenda containing multibrowse links to information relevant to the meeting can be put together ahead of time. This allows information to be brought up on the most convenient screen as the meeting progresses.

Many of our meetings have a very similar flow-- we do some work independently then get together to share this work and discuss it in detail. If all the users posted their independent research on the Web, and sent the links to the meeting coordinator, the coordinator could create an HTML page that provides a drop down list of the available SmartBoards in the iRoom for each link on the agenda Web page. This Web page could then be brought up on one or more computers and used by members of the group to multibrowse the listed links to any display in the room. Figure 4 is a mockup of such a page.

One of the most obvious uses for multibrowsing is to coordinate a presentation across multiple screens. We present here two different styles of presentation that we have used in the iRoom. The first is the more traditional where the presenter steps through their information slide by slide. Multibrowsing enables this style of presentation to be coordinated across all of the available screens instead of just one as is typically the case with most PowerPoint style presentations. The second style of presentation is 'hierarchical,' or 'non-linear.' In this case by bringing the arbitrary inter-linking facility of the Web to multiple screens, multibrowsing allows presenters to create presentations that can pull up more detail on screens in the room depending on the audience for the presentation.

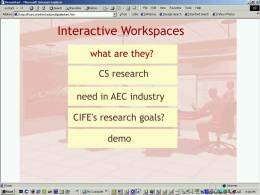

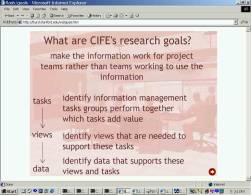

The iRoom is used as a conference room by several associated research groups at Stanford, one of which is the Center for Integrated Facilities and Engineering (CIFE) [LIS]. The CIFE group is part of the Civil Engineering Department at Stanford and is working on improving the planning of large-scale civil engineering projects. They are experimenting with CSCW environments like the iRoom to understand how such environments facilitate meetings between architects, building contractors, and planners. We worked with this group in building a multibrowsable presentation for their meetings. In addition to plain vanilla HTML, this presentation uses other client-side web technologies such as Java and Flash. Our experiences with multibrowsable presentations such as this for almost a year have affirmed our belief in the utility of the multibrowse system.

Figure 5(a) - SmartBoard1 Display |

Figure 5(b) - SmartBoard2 Display |

Figure 5(c) - SmartBoard3 Display |

The CIFE presentation is designed for a single presenter who uses the three SmartBoards and the table mounted display. SmartBoard1 displays the "lead" slide, which allows the presenter to control the information displayed on all the SmartBoards. Thus, the lead slide contains multibrowse links that causes the other presentation slides (which are Web pages) to be displayed on the other SmartBoards. The lead slide contains a broad overview of the project and the presenter brings up detailed information about each of these categories on the remaining SmartBoards as he proceeds through the presentation. For example, when the presenter clicks on the hyper-link "CIFE's research goals?", Web pages describing the research goals are opened on the other SmartBoards (Figure 5). Thus, a Web page showing the goals of the project is displayed on SmartBoard2 and an artist rendition of what the iRoom would look like in the future is displayed on SmartBoard3. Thereafter, the presenter proceeds to the next category which is "demo". A click on the hyperlink “demo” causes all the other displays are updated to display the Web pages that are needed for the demo.

Figure 6(a) - Start Page Displayed on SmartBoard1 |

Figure 6(b) - Presenter Multibrowses Link on SmartBoard1 |

Figure 6(c) - Linked Page is Opened on SmartBoard2 |

Figure 6(d) - Presenter Selects Link on SmartBoard2 |

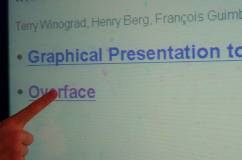

Figure 6(e) - Close Up of Imagemap Link on SmartBoard2 |

Figure 6(f) - Linked Page is Loaded on SmartBoard3 |

Another form of presentation is a nonlinear, or hierarchical, presentation, which leverages multiple displays for displaying information at several levels of detail simultaneously. An example non-linear, or hierarchical, presentation starts with a page containing links to the main topics to be covered in the presentation displayed on one SmartBoard. Each of these links then point to similar pages, which in turn contain links to sub-topics. Such a structure allows the presenter to follow a number of different presentation paths very easily. In the example we cite here, the start page contains the main topics, ‘Graphical Presentation’ and ‘Overface’ (Figures 6a and 6b). The presenter selects ‘Overface’ (Figure 6b) and this brings up the page that lists the various parts of Overface on SmartBoard2 (Figure 6c). The presenter can then select any of the links on SmartBoard2 (Figures 6d and 6e) to bring up the linked page on SmartBoard3 (Figure 6f). If the presenter had instead selected ‘Graphical Presentation’ on the start page, a Web page listing the subtopics of ‘Graphical Presentation’ would have been displayed on SmartBoard2. In fact, at any time the presenter can go back and display other paths. This pattern of progression gives the presentation a tree-like structure with nodes of depth 1 being displayed on SmartBoard1, nodes of depth 2 being displayed on SmartBoard2, and the leaf nodes being displayed on SmartBoard3. To create such a presentation, the presenter creates multibrowse links instead of regular links, and is not required to write any code or scripts.

One of our goals for multibrowsing was to be able to construct prototypes of more complex ubiquitous computing systems. This hypothetical example shows how by creating some custom server side extensions, one can use multibrowsing to display dynamic content across multiple displays and devices without having to program custom viewers for all of the platforms in the environment.

The target scenario is as follows: the management team of a company discussing sales trends wishes to view pie charts and histograms depicting sales of different product items. Selecting any date should cause a pie chart and a histogram showing the sales on that day to be displayed on two different displays. This scenario can be realized using the multibrowsing paradigm as shown in Figure 7. A single server-side program is written (using CGI, servlets, etc) that is capable of generating a pie or a histogram on demand given a date. A custom multibrowse page can be constructed that contains multibrowse links for each date. The links encode a request to the remote browser to load a GET request for the server-side application to generate a histogram for the given date. Additionally, they cause the local browser to load a GET request for the server-side application to generate a pie chart for the same date.

A traditional implementation of this application without using the Web and multibrowsing infrastructure would probably install viewer processes on the devices that communicate with TCP/UDP sockets to synchronize with each other and to ship the generated pie and histogram charts across the network. Infrastructure would have to be created from scratch for every such application. Depending on the implementation, adding a third view (such as a graph) or porting this implementation to a completely different environment would almost certainly be more complicated than the multibrowse-based implementation. This illustrates how the multibrowsing paradigm leverages Web standards and technologies (such as the ubiquitous Web browsers, MIME, associated plugins to view image data, server-side processing to dynamically generate data, and standard Web protocols for the actual transfer of data) to simplify building applications that need to move information around.

It is worth noting that the use of standard Web browsing technologies for the design and implementation of multibrowsing allows it to be used on any web enabled device. In particular, no custom software needs be installed on the devices for submitting multibrowse requests to other displays using multibrowse links. (Of course, we need multibrowse daemons to be installed on the intended recipients of multibrowse requests). Thus, we could have used Windows CE devices (with no custom software installed) for any scenario using multibrowse links (but not the scenarios using the plug-in), since the only requirement for multibrowsing is the presence of a web browser. Conceptually we could also have used a Palm OS based device. Similarly no changes are needed to the presentations, since multibrowse links are inherently independent of where they are invoked from.

This section goes into the details of the various components of the system, of which there are several that comprise the multibrowsing system. The entire system is built on top of the Event Heap. The multibrowse daemon program runs on a target machine and relays URLs to the browser on that machine. The multibrowse servlet allows the multibrowse link functionality by transcoding fat URL's into multibrowse event submissions. The multibrowse plugin extends the browser to allow the redirection of existing web content. Finally, there are two tools, multibrowse forward, which redirects multibrowse events to new targets, and multibrowse submit, which allows multibrowse events to be sent from the command line. Figure 8 below shows the connections between the various components which are discussed throughout the rest of the section.

As described in section 2, the core functionality of multibrowsing is implemented by coordinating the behavior of several copies of unmodified Web browsers. This is done using a loosely-coupled communication substrate called the Event Heap. The Event Heap is a shared "blackboard" of tuples, or a tuple space (following the model of Linda [GEL]), where a tuple is just an ordered collection of typed and named fields. Communication with the Event Heap occurs over TCP/IP-based protocols; software entities can post tuples to the tuple space or query the tuple space for tuples matching a specific template. On top of this mechanism we have provided a simple taxonomy of application-level events, one of which is used for multibrowsing. (Note that our use of the term "event" refers to high-level events such as "open URL", not low-level events such as those manipulated by traditional GUI event queues.) One important feature of events is that they have a finite time-to-live after which they are removed from the Event Heap. This is important for the multibrowse system to insure that events targeted to a non-operational display do not cause unexpected behavior when the display comes back up.

The Event Heap is built using TSpaces, a research package from IBM Almaden Research Center, as a starting point. Although the system's core is implemented as a set of Java classes, the loose structure of the event tuples and the simplicity and paucity of functions in the Event Heap API has made it easy to integrate with other languages and programming environments. Thus it is not necessary to author and link one's own code in order to use the Event Heap. In particular, in the following sections we will describe the middleware components (referred to in section 2) that allow Web browsers to post and "subscribe" (indirectly) to events. We chose the tuple-space-based Event Heap because it is flexible, robust, and easy to use, and the solution we have chosen for building a variety of other Interactive Workspace applications whose description is outside the scope of this paper. However, multibrowsing itself can be built on top of any adequate many-to-many communication infrastructure (e.g. multicast-based tools such as MASH [MCC]).

The underlying structure for multibrowsing is based on Event Heap sources and receivers for the Multibrowse event type. The event is relatively simple, and specifies a URL to be loaded on some target machine. The TimeToLive for multibrowse events is set at 15 seconds which allows displays that are not active or just coming up at event submission to respond to the request. The following table shows the key fields for the multibrowse event type:

| Field | Purpose |

| Integer SourceID | Unique ID of the sender of this event |

| Integer EventType | EventType identifier for multibrowse events (Value=1345) |

| Integer TimeToLive | How long the event persists in the Event Heap. Set to 15 seconds. |

| Integer TargetID | Unique ID of the display or device to load the URL |

| String CommandToExecute | The URL to be loaded (this can also contain other commands to be executed on the target machine, but this functionality is not used for multibrowsing) |

| String RunMode | Specifies whether to load the URL full screen, minimized, in current window, etc. (Currently only used on Windows platform) |

Multibrowse events may be submitted or consumed by any application that uses the Event Heap, which makes it easy for new applications to be created and integrated with the existing multibrowse infrastructure. It is left to the individual applications to honor the intended semantics.

The multibrowse daemon, or multibrowsed, waits on a machine for multibrowse events, then relays the URL to the installed browser on that machine. Currently we support Windows and Linux, but the application is Java based so it could be easily adapted to other platforms. In the Windows environment the daemon works by using Windows shell extensions, which allow mappings to be made between content types and applications. When a URL is passed as the content to open, Windows will load the URL in the default browser. In Windows, the RunMode flag, which controls the maximize/minimize state of the displayed Web page, is also honored. In Linux, the daemon currently works only under X windows with Netscape. When a URL is received, the 'netscape -remote' command is used to load the page in an existing browser instantiation, or if no browser is running, a new copy is started with the given URL. Although not specifically useful for multibrowsing, the daemon will accept non-URL strings in the CommandToExecute field, in which case it runs the string as if it were a command. This allows Web pages to trigger applications to run on remote machines and can be used with scripting and mbsubmit (discussed in section 4.6) to coordinate the display of information across multiple screens. (Note this is a security issue which we partially handle by restricting which hosts can submit events through the multibrowse servlet).

The multibrowse servlet allows the submission of multibrowse events from Web browsers. Thus, mutlibrowse event submission can be achieved by posting a form containing values for the fields of the multibrowse event to the servlet. Specifically, the form has fields for TargetID, CommandToExecute, and a special field called redirectURL. The following "fat URL" is a form submission to the servlet with TargetID = 104, CommandToExecute = "http://www.cmu.edu", and redirectURL = "http://www.stanford.edu".

http://iw-room:8080/servlet/ehservlet?TargetID=104&CommandToExecute=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.cmu.edu &redirectURL=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.stanford.edu

As mentioned earlier, we refer to links containing such fat URLs as multibrowse links. Clicking a multibrowse link that contains the above URL causes the servlet to submit a multibrowse event with TargetID = 104 and CommandToExecute="http://www.cmu.edu". The servlet also redirects the browser used for the form submission to "http://www.stanford.edu". (The utility of this feature will be explained below.) Hence, the net effect of clicking the above multibrowse link is to cause the current browser to display "http://www.stanford.edu" and the browser on device 104 to display "http://www.cmu.edu". Figure 9 illustrates the sequence of steps involved in this process. Note that the figure is primarily meant to illustrate the working of the multibrowse servlet, and hence omits other components of the multibrowse architecture.

To create custom sites and presentations for multi-display environments, users construct Web pages with embedded multibrowse links that when clicked, automatically cause Web pages to be opened on other displays as shown above. Users typically construct these "multibrowse links" by posting the desired event manually using the Web form and noting the URL constructed by the browser. A more convenient approach is to use POST requests with hidden fields. We have found the current methodology for creating multibrowsable sites and presentations adequate for a research prototype. However, for actual production use by non-technical users, a more friendly user interface to assist in constructing the URLs is needed.

The redirect URL field is extremely useful while constructing multibrowsable Web sites and presentations. For example, a user creating Web pages for a presentation on two touch-sensitive displays may want the "next" button on any slide to cause the next slide to appear on the primary display and the current slide to appear on the secondary display. To achieve this function, the user sets the redirect URL for the "Next Slide" link to the following slide, CommandToExecute to the current slide, and TargetID to the identifier of the secondary display.

As of now, the servlet supports submission of only one multibrowse event per form post. Modifying the servlet to allow multiple event submissions for a single form post is a simple and useful extension. This extension would enable a single multibrowse link click to bring up various Web pages on many displays simultaneously. (Currently, this functionality is achieved by creating links that generate a multibrowse event to invoke a script on some target machine.)

Security is an important concern with multibrowsable Web pages since the servlet can potentially allow multibrowse event submissions from unauthorized parties. As mentioned earlier, the only security mechanism implemented is to allow multibrowse event submissions only from trusted IP addresses within the local domain.

Backward compatibility is important for the success and utility of a system. With this in mind, we explored ways of Multibrowsing existing web pages. Our solution is to use a browser plug-in to integrate existing content with the multibrowsing system. The most intuitive place for adding this functionality we found to be in the context menus triggered by right clicking the mouse, since the context menu is also used to open links in a new browser window. We added two new menu selections that get activated depending on the context of the menu. One of these allows the user to send the current web page to any other display in the iRoom, while the other gets allows the user to multibrowse the selected link (see Figures 1 and 2). When either of these options is selected the user is presented with a pop-up window containing an iconic representation of the displays in the iRoom (see Figure 3). The user can then select the display to which he wants to multibrowse the link or the current page.

Most modern browsers expose an API that allows programmers to write and attach custom event handlers. In order to extend the multibrowse system, we added handlers for the events generated by the users" selecting options in the context menu. These handlers used ordinary URLs and user feedback to create multibrowsable links on the fly.

For our prototype system, we used Microsoft Internet Explorer 5.0. We wrote a small installation program that used the Windows Registry to modify Internet Explorer (IE) and that installed two Visual Basic Scripts to handle Multibrowse events generated by the user. (this program can be executed directly from a Web page, as is the case with most regular browser plug-in installers). These Visual Basic scripts are invoked by IE and are passed the selected URL (of either the selected link or the current page). The multibrowse system then does an HTTP GET to the Event Heap Servlet and transfers all the information required for multibrowsing. While our present scripts have been written for the iRoom and hence contain iRoom specific information, it would be trivial to modify them for use in another room. They can also be modified to read from an initialization file so that they generate a representation of the multi-display environment for the user's selection.

The same system can also be implemented for IE by writing a Browser Helper Object (BHO) or in Netscape by writing a Netscape Plug-in. If the browser is modified using one these methods then the system could be designed such that the BHO or the Plug-in communicate with the Event Heap directly rather than through the Event Heap Servlet. Further, BHOs or Plug-ins could also be written to support Multibrowsing for existing non-HTML content such as Flash. Conceptually, these modifications can be made to any Browser that offers an event subscription interface to which an event handler can be added, regardless of platform.

The multibrowse forwarder, or mbforward, can be run on any machine which can attach to the same Event Heap as the other components of a running multibrowse system. It contains a mapping of virtual TargetIDs to new TargetIDs, and consumes all multibrowse events sent to one of the virtual target IDs and resends them with the corresponding new target ID. This allows multibrowsable Web pages to be created using virtual identifiers for screens or devices, say Screen1=101, Screen2=102, and Screen3=103, and then used in differing environments. For this each environment mbforward would be set up with the mapping of the virtual screen identifiers to the actual targets in the room where the URLs are to be displayed. Mbforward can also be used to compensate for equipment that is down, for example by mapping events for both screens 1 and 2 to the same display. Currently the program loads the mappings from a simple configuration file, but it could also load them from a central database for the environment.

The final piece is the multibrowse submit, or mbsubmit. It is a simple command line utility that allows the user to specify one or more multibrowse events to be generated. It can be used to test the system, or can be called from scripts to allow more complex multibrowse behavior (for example, a script could be called from multibrowsed which generates different multibrowse events depending on the current configuration of the Interactive Workspace).

As mentioned earlier, the system need not have been built on top of the Event Heap. Our choice to build on top of it has certain advantages, though, which have already proven helpful in day to day use. The first is that we see relatively robust behavior since there are no direct connections between event sources and event consumers. So, if a target machine is hung, not running multibrowsed or down, the event for that machine simply times out without effecting the rest of the multibrowsing system. Also, if a machine is in the process of coming up when a multibrowse event is submitted, it will still receive the event and be able to display the Web page provided the event hasn't timed out. The extensible typing system also allows new fields to be added to multibrowse events by future applications without breaking the rest of the system. We actually added the RunMode field, for example, after the system had been running for several months, without breaking the existing system.

The idea of sharing and coordinating information display across multiple screens is not new. The iLand environment built at GMD-IPSI in Darmstadt [STR] is physically similar to our iRoom. Their BEACH software platform is built in Smalltalk, and is based on an object-oriented framework called COAST for synchronizing multiple simultaneous access to objects. This enables them to develop sophisticated groupware environments that base information display on object synchronization, but it does not support standard Web content, and prototyping new interaction methods requires programming.

The Classroom 2000 project at Georgia Tech has also dealt with coordinating information display [ABO]. They were specifically coordinating the playback of a PowerPoint presentation between a lecturers machine and they machines of individual students taking the class. While this system could be extended to allow more complex control between PowerPoint presentations on multiple machines, this is less flexible than being able to use arbitrary Web content.

Push technologies have been well explored in wide area networks [FRA]. Typically, they are used for delivering personalized content to end-users. However, the issues and applications differ in scale and intended use between multibrowsing and wide-area push technologies.

Recently there have also been several papers published on "guided browsing" [GRE] [HAU] [ROS], which bears some resemblance to multibrowsing. In this case one browser is slaved to another to allow a person on one computer to guide someone on the other computer through the web. In some cases browse sessions are recorded so that the sequence of page accesses can be played back at a later time. While both multibrowsing and guided browsing involve controlling the page loaded by a remote browser, multibrowsing is more flexible in that there is no direct client-slave relation between browsers.

Multibrowse events as described in this paper are non-portable for two reasons:

To address problem (1), we are adding a "room information database", which contains information used by many iRoom applications including multibrowsing. The room database will include a mapping of logical display names (e.g. "main", "left wall", "table top", etc.) to physical displays. Multibrowse events can then name logical displays, with the mbforward machinery described in section 4.6 rewriting events on the fly to effect the mapping. How best to resolve conflicts, such as naming more displays in multibrowsable content than exist in a particular environment after reconfiguration, is a subject we are exploring.

Problem (2) can be addressed by interposing an HTTP proxy in the multibrowse environment. All HTTP requests (multibrowse or not) could be filtered through this proxy, which would look for multibrowse links in the HTML content and rewrite the links to name the appropriate local Event Heap servlet. Although we have not built it, the use of a transformational proxy for such techniques has been well explored [FOX1] [FOX2] and we believe it would be straightforward to add this functionality to multibrowsing.

In section 4.5 we described our enhancements to Internet Explorer to enable multibrowsing of existing non-multibrowse-aware sites. A similar capability could be added to browsers that do not support similar client enhancements through the use of a transformational proxy. This proxy would intercept HTML content coming from servers, and for each embedded link L in the original content, the proxy could rewrite L to cause the appropriate multibrowse events to be submitted if L is traversed. If the client is sophisticated enough to support client-side scripting such as JavaScript, the proxy can insert JavaScript code that causes a popup menu to appear when L is clicked, resulting in a user interface more similar to that described in section 4.5. At the expense of perturbing visual layout of the page, less sophisticated clients could be supported by adding n inline links after L, each of which would cause L to be visited on one of the n available displays. For example, on a 4-display installation, such a transformation might have the following effect:

| Original content Visit the Graphics home page for more details. |

After transformation Visit the Graphics home page [Screen 2][Screen 3][Screen 4] |

Variations on this theme, such as using clickable imagemaps instead of multiple text links, are also possible.

Currently we must author multibrowse-aware sites by manually constructing the appropriate link URL's. This is appropriate for developers, but for multibrowsing to enjoy widespread use, existing authoring tools can be modified (or supplemented with new tools) to support the creation of multibrowse-aware sites. We are not currently focusing effort on this area but would welcome contributions.

"Guided browsing", as mentioned in related work, could be combined with multibrowsing. A "multi-screen slide show presentation" could be easily constructed by recording (logging) a sequence of multibrowse events and then replaying the session. Since the Event Heap allows multiple passive listeners for each event type, we could construct a recorder program that can capture all multibrowse events in a session, then play them back to create a multi-display presentation. This would generalize and enhance the capabilities of existing Web-based presentation systems in multi-display environments.

We have found multibrowsing to be a useful extension of the information browsing metaphor to multiple displays in ubiquitous computing environments. Because it works by coordinating the actions of multiple independent browser programs, we realize several key benefits:

A non-obvious benefit we have experienced is the ability for a single user to browse privately on her own PC or handheld, but have the ability to share relevant discoveries with other collaborators by using multibrowsing to immediately "redirect" the relevant Web page to another public display in the iRoom. We have exploited this benefit in informal collaborative research meetings as well as with purpose-designed multi-display presentations.

The most significant current challenges in evolving our multibrowsing system revolve around portability. Specifically, until we deploy logical display name indirection as described in the Future Work section, our multibrowse-aware sites have display names hard-coded into them, making the sites non-portable across ubiquitous computing environments with differing screen geometries. Similarly, multibrowse sites must be manually edited when our own iRoom is reconfigured (i.e. if a large fixed display is added or moved).

Multibrowsing is certainly not the only mechanism required for successful adoption of ubiquitous computing. For example, purpose-built multi-display applications may be available that offer a more streamlined presentation, exhibit better performance, or are better able to adapt to the specific characteristics of different displays (e.g. high resolution "mural" displays vs. handheld-PC screens). Furthermore, for interactive presentations, multibrowsing is limited to the user interaction mechanisms that can be conveniently implemented using Web browsers; more sophisticated interaction may require the use of purpose-built applications. Despite these limitations, we believe multibrowsing demonstrates an effective set of mechanisms for extending the highly successful Web browsing metaphor to multi-display ubiquitous computing environments, and we hope it will be a catalyst in taking ubiquitous computing to the next level of utility for many casual users.

Pat Hanrahan helped us develop the initial concept of multibrowsing. Terry Winograd and Kathleen Liston helped create some of the presentations used in the examples section. Andy Huang offered helpful comments on the paper. Thanks also to the other faculty, staff and students who have helped on the Interactive Workspaces project over the past year.

[ABO] G. Abowd, "Classroom 2000: An Experiment with the

Instrumentation of a Living Educational Environment," IBM Systems J., Vol. 38,

No. 4, Oct. 1999, pp. 508-530.

[FOX1] Armando Fox, Steven D. Gribble, Yatin Chawathe and Eric A.

Brewer. Adapting to Network and Client Variation Using Active Proxies: Lessons and

Perspectives. IEEE Personal Communications (invited submission), August 1998

(Special issue on adapting to network and client variability)

[FOX2]Armando Fox, Steven D. Gribble, Yatin Chawathe, Anthony Polito,

Benjamin Ling, Andrew C. Huang and Eric A. Brewer. Orthogonal Extensions to the WWW

User Interface Using Client-Side Technologies. In Proceedings of UIST 97, Banff,

Canada, October 1997.

[FRA] M. Franklin and S. Zdonik. Data in your face: Push technology

in perspective (invited paper). In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference

on Management of Data (SIGMOD98). ACM Press, June 1998. http://www.cs.umd.edu/projects/bdisk/inyourface.ps.

[GEL] David Gelernter. Generative communication in LINDA.

ACM Transactions on Programming Languages and Systems, 7(1):80--112, January 1985.

[GRE] Jim E. Greer and Tim Philip, Guided Navigation Through

Hyperspace, Proceedings of the workshop "Intelligent Educational Systems on the World

Wide Web", 8th World Conference of the AIED Society, Kobe, Japan, 18-22 August 1997.

[HAU] Franz J. Hauck, Supporting Hierarchical Guided Tours in the WWW,

In Proceedings of the Fifth World Wide Web Conference.

[LIS] Liston, K., Kunz, J., and Fischer, M., “Requirements and

Benefits of Interactive Information Workspaces in Construction,” The Proceedings of

the 8th International Conference on Computing in Civil and Building

Engineering, Stanford, USA, 2000.

[MCC] Steven McCanne, Eric Brewer, Randy Katz et al. Toward a

Common Infrastructure for Multimedia Networking Middleware. Proc. 7th Intl. Workshop

on Network and Operating Systems Support for Digital Audio and Video (NOSSDAV 97), St.

Louis, MO, May 1997 (invited paper).

[ROS] Martin Röscheisen, Christian Mogensen and Terry Winograd,

Beyond Browsing: Shared Comments, SOAPs, Trails, and On-line Communities, Proceedings of

the Third World Wide Web Conference: Technology,

Tools and Applications, April 1014, 1995.

[STR] N.A. Streitz et al., i-LAND: An interactive Landscape for

Creativity and Innovation. In Proc. ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems

(CHI '99) , Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., May 15-20, 1999. ACM Press, New York,

1999, pp. 120-127.

[WEI] Mark Weiser, Some Computer Science Issues in Ubiquitous

Computing, CACM, 1993.